RRR mode for new RBI gov: Sanjay Malhotra's focus should be rates, rupee, and regulation

[CAPTION] The newly appointed Reserve Bank of India (RBI) governor Sanjay Malhotra leaves after addressing a press conference, in Mumbai on December 11, 2024.

Image: Indranil Mukherjee / AFP[/CAPTION]

There is never a right time for any central banker posting and Princeton-educated former revenue secretary Sanjay Malhotra will agree. The veteran bureaucrat took charge as Reserve Bank of India (RBI) governor on December 11, for a three-year term, replacing predecessor Shaktikanta Das. The latter took charge in 2018 and had the second-longest tenure (six years) as RBI governor, tackling the toughest phase of keeping economic growth on track during the national lockdowns due to the pandemic.

_RSS_Raghuram Rajan, former chief economist of the International Monetary Fund (IMF), was RBI governor for three years ending in September 2016, followed by Urjit Patel, an IMF economist, who oversaw demonetisation of the currency, before stepping down abruptly by December 2018.

There was some chatter in banking circles that Das would get an extension as he was a trusted hand. “However, in recent weeks, a stark divide seemed to have emerged between the government and the RBI on the need for countercyclical monetary policy, with both, the finance minister and commerce minister criticising the RBI for keeping policy tight on account of high inflation in a few food items and Governor Das who stuck to his guns in the December 6 policy meeting, and pushed for a continued hold,” Nomura’s chief economist Sonal Varma says in a note to clients on December 9.

Not much is known about Malhotra’s views on the current economic outlook and policies for India relating to interest rates and the movement of the rupee, which has depreciated to a historic low of 84.7 to the dollar, dipping by 2.3 percent in the past year.

On taking charge, Malhotra told the media: “All businesses, all people… they do need this (policy) continuity and stability rather than day-to-day kind of a policy. As we have to be conscious of the fact that we do maintain continuity and stability, we cannot be stuck to it, and we have to be alert and agile to meet challenges.”

Focus on RRR

Malhotra would need to focus on a combination of a new RRR in the making—rates, rupee and [proactive] regulation—to ensure that stability continues to be maintained, much like what Das managed to achieve during his tenure.The start of an interest rate cutting cycle is much awaited, with the hope that it will spur growth. This remains the topic of conversation for a deeper debate: If interest rates are lowered, how can one be sure of growth. The last time the repo rates in India were steady at 4 percent was between March 2020 to April 2022—the pandemic years.

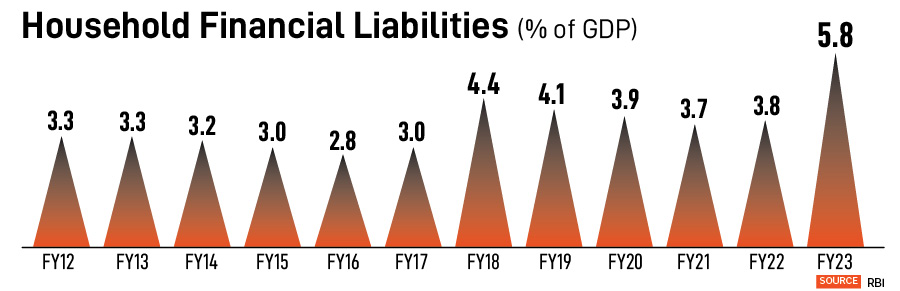

Sakshi Gupta, economist at HDFC Bank, suggests that it is not that the monetary policy is not useful in pushing for growth. According to her, RBI data shows that for households, leverage has increased significantly since the pandemic. Household financial liabilities as a percentage of GDP is seen at 5.8 percent in FY23, a highest in 16 years (see chart). FY24 data was not available.

“This data shows that the way families are consuming… they are more comfortable to take on leverage. They have become more sensitive to interest rates. A rate cut or the alignment of interest rates with a policy rate which is more supportive of growth is a task ahead for the new governor,” Gupta tells Forbes India.

Most economists, including those at Bank of America (BofA Securities) and JP Morgan India forecast a 25 basis points cut in interest rates in February2025’s monetary policy meeting. But Gupta does not see this as the start of a prolonged rate cut cycle. “It will be a readjustment, normalisation to sustain growth at a particular level,” she says.

Nomura’s Varma, who also suggests an interest rate cut in February 2025, says there are potential changes that could occur under the new RBI governor.

“There is a likely shift towards a more accommodative monetary policy. The friction between the government and the RBI on high borrowing costs amid weaker growth momentum is well known. With the new RBI governor from the ministry of finance and with fresh thinking at hand, a rate cut at the February monetary policy meeting is now likely cemented.”

After January 15, the RBI’s monetary policy committee (MPC) will “have a new look and feel”, Varma says, with the tenure of RBI’s deputy governor Michael Patra ending.

Varma adds that Malhotra and team will need to decide on the direction of macro-prudential policies. “Given Malhotra’s background in the department of financial services, it is possible that amid slowing bank credit growth, macropru policies are less pro-cyclical,” she says. She expects a 100 basis points in total cuts to a terminal rate of 5.5 percent by end-2025.

While balancing inflation and growth remains the key focus for every central banker, an eye will have to be kept on how urban demand pans out. Consumption demand for households in urban India is slowing and consumer goods sales, from recent quarters, reflect this.

Gupta says India is “coming off a surge (post the pandemic) and it is a mean reversion”. India has also lower wage growth and job losses across some sectors, which have impacted income generation and spending, Need for a stable rupee One of the biggest challenges which will keep Malhotra and his team occupied will be balancing the stability in the rupee while managing domestic liquidity conditions. Experts forecast more pressure and depreciation for the rupee against the dollar, assuming that tariff restrictions will come in the Trump 2.0 regime next year. This will mean the US Federal Reserve possibly slowing down rate cuts, as monies start to flow back to the United States.

Also read: In no rush to go back to the world of ultra-low interest rates: US Federal Reserve

“It means a depreciating pressure for the rupee. Any intervention to curtain volatility on the rupee—for example, the spot market by selling dollars—will mean removing rupee liquidity from the system,” HDFC Bank’s Gupta says. “The challenge is to let the rupee depreciate to maintain competitiveness but also to prevent any panic run-offs. The RBI will need to manage the liquidity implications of any interventions they do,” she adds.

Bank of Baroda’s chief economist Madan Sabnavis believes the interventions to support the rupee were justified. “The challenge will be managing volatility, considering that there will be FDI and FPI outflows and trade restrictions. The RBI will have to be more proactive. It cannot allow the rupee to find its own level,” Sabnavis tells Forbes India.

Malhotra is placed in a sweeter spot than earlier governors, considering that India’s foreign exchange reserves were pegged at $658.09 billion for as on November 29, according to RBI data. The build-up in forex reserves will give the RBI enough ammunition to protect the rupee, economists say. The economy is better placed than in 2013, when the Taper Tantrum took place, resulting in the sharp depreciation of the rupee against the dollar.

“The RBI has been successful in managing inflation and ensured that it has not spilt over into leading to broader inflationary and wage concerns,” Gupta says.

Varma says the RBI has always sought to build its forex reserves buffer (precautionary motive) and smooth out volatility—two aspects that may continue under the new management. However, it is possible that a bit more flexibility is allowed in currency fluctuations, going forward, as compared to the relatively tighter leash seen over the last one year and more.”

Food inflation will wane

While the RBI will be focussed on ensuring that inflationary pressures do not rise, economists are confident that this is unlikely to happen. Food inflation pressures will reduce and they do not see a broad basing of food inflationary pressures spilling into core inflation.

Sabnavis also agrees that food inflation will start to drop off in the coming months. The interpretation of inflation levels and future inflation outlook will be important to understand, he says, with the entry of the new RBI governor.

Saying it straight

One of the clearest takeaways from Das’s regime was his communication to the industry and public at large. When concerns were spotted, the regulator issued the red flag, even to the biggest banks such as HDFC Bank and Kotak Mahindra Bank. Others such as Mastercard and Paytm were not spared either.

Malhotra’s style will be different. But Sabnavis does not believe that there could be any easing in regulations, whether towards banks or fintechs. “The regulator cannot be caught napping. There has to be proactive regulation, as we saw during Das’s tenure,” says Sabnavis.